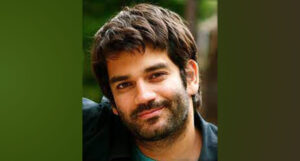

According to the International Section of th38 Tehran International Short Film Festival, Bady Mink AmourBorn in Luxembourg, she works as an artist, filmmaker, and producer in Luxembourg and Vienna.

The famous Austrian Filmmaker Said:

For me, the innovative power of cinema – and especially of experimental cinema is a central motor for the arts and for society – and at the same time a mirror and counterpart of social conditions and their changes. Elementary for my films is to cross borders. Boundaries between artistic disciplines, boundaries between genres, and also between short film and full-length film, between feature film, documentary film, animated film, and experimental film. And boundaries between science and art, between art and politics. When writing a script, my themes go through a process that is probably similar to the process of human food digestion: selection, condensation, alienation, transformation, and metamorphosis. In doing so, I try to build up fields of tension between form and content, between abstraction and figuration, between surface and space, time dilation and acceleration, order and coincidence, harmony and restlessness, unity and diversity, inside and outside, and most importantly: unambiguity and ambiguity.

The technique of condensation, of simultaneous storytelling on several levels, ensures that my films can be interpreted very differently by the viewers and it turns long complex stories into short films.

In my films I want to make visible, what in normal life is invisible – that’s one of my challenges. To find ways to do it, I am in all of my films working with different techniques like stop-motion, pixillation, time-lapse, slow motion, and also with different animation techniques.

But I try to avoid making these techniques too visible. It is important to me that the audience can concentrate on what is being told and suggested – and not be distracted by the technique.

During my researches, I came across the architect Adolf Loos, a pioneer of creative constructions in space. In order to get to understand his spatial thought processes, I wanted to render it visual, and which medium could be more fitted for that than film? For this, I used a model Adolf Loos made in 1923 for Mexico City’s city hall. The individual parts of the model could be assembled in various ways.

In the film, I assemble these parts in various ways and was even able to use them to build a city in which the streets run like neural pathways through the canyons of houses. In making the film with its many different experimental arrangements, I was able to learn to understand Adolf Loos’ spatial thinking and make it visible in the film.

I wanted to show with this how art transforms itself from the idea onto paper and from there into space and time and – in the case of non-realization, it is pressed back into the paper and from there wanders into destruction.

In MÉCANOMAGIE – you could say that I wanted to make visible the history of the earth beneath my feet; to show all that is buried and hidden – and how it is related to the people who live on the earth.

I built the script in the form of a repeating cycle, the natural cycle of SEEDING, GROWING, and HARVESTING. Every scene in MÉCANOMAGIE is subject to this cycle: Children growing out of the earth, cakes growing on trees, Roman letters dug up to bring us messages, living stones holding memories, a peasant woman whose language has been petrified, and so on.

The dream and the unconscious also play a big role in my films – also in MECANOMAGIE. When I wrote the script and started filming, I didn’t know I was pregnant. One film scene shows small children growing out of the ground. A few months later, right at the premiere of the film, my son was also born. Many then believed that I had deliberately written this child scene into the script, but that was not the case.

In order to study art, I leaved my country looking for art academies in different countries and saw all these postcards representing the different countries and noticed that each country had its own style of representation. I chosed the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna to study and to go by the postcards, Austria was a country in which the sky was always blue, the landscape untouched and the villages rustic – everything was completely idyllic.

I loved especially the used postcards, from the flea markets. They showed the idealized image of Austria on the front but, when I turned the postcards round, they gave a quite different picture. The texts from the postcard writers told the negative stories about continuous rain, ski accidents, bad food, broken hearts but also from child abuse, the persecution of minorities, and problems with racism.

So I decided to make a film about the two sides of the postcard, to find out more about the other side of Austria, the hidden and suppressed one.

For this film with the title, IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE EYE I collected over 15.000 postcards at flea markets and antique shops; 1.800 of them were used in the film. The confrontation between the old images, many of which were retouched, and the reality led to sudden avalanches and other surprises. Sometimes the reality matches what is shown on the postcard, but in many cases, mountains shown at certain locations aren’t really there.

The world depicted on Austrian postcards is cozy and clean. Even the ski-lift stations seem to be made of wood, and the modern Alpine huts are built in a rustic style, leaving the impression that they’ve been there for ages. In the past the perilous mountain roads were depicted proudly, but as more and more people began writing about traffic jams on the reverse, all roads disappeared from the other side.

Apart from wanting to discover more about the hidden side of Austria I was interested in postcards as a way to put a huge landscape on a small paper surface. What happens to a country and a landscape when it is shrunk and flattened so as to fit on the easily consumed and transportable format of the postcard?

In the Beginning was the Eye deals extensively with the question of the construction of images and of images (in this case the image that Austria gives itself).

It stands for a central moment in my artistic work, the inter-and transdisciplinarity. I find that in the combination of different disciplines a cross-fertilization arises and a work can thereby gain more sharpness and tension, as well as a greater richness and complexity.

During the script development of IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE EYE I had a very enriching exchange with the scientists of the Cultural Landscape Programme of the Austrian Ministry of Science. I was able to work with 20 scientists from different disciplines and incorporate their insights and feedback into my script.

In the Beginning was the Eye was the first of my films to use language as a medium. But not like in mainstream cinema, where the story is largely told through dialogue, here I wanted to use language as an art form, as a poetic element, as well as a musical element. For this, as in all my films, the image should take over the role of the narrator.

I also used language here as a graphic element and asked the poet Ernst Jandl to write graphic poems for the walls and furniture of the film flat. The writer Friederike Mayröcker also contributed poems, which she herself breathed onto the soundtrack in a whisper.

Instead of an actor, I chose the poet Bodo Hell as the main character because his expression embodied the ideal figure of a poet and researcher.

But since Bodo Hell, as a poet, had no actor’s training and therefore could not have changed his expression in front of the camera on command, I developed a technique that gave him much more time to adjust his facial expressions and gestures during the shoot.

I shot him at six frames per second instead of 24, while at the same time he moved four times slower than in reality. This allowed him to act 4 times slower, which gave me more time to give stage directions for his acting. In the speed of Bodo’s movements, this makes no difference in the film, but the viewer sees the fourfold concentrate of Bodo Hell’s emotional outbursts or his pensive wrinkles and this gave his acting more quality and more depth, as he had a 4x enhanced facial expression in the film.

The film is shot alternately in a single frame, at six frames per second, in slow motion and timelapse. In some sequences, time races by accelerated in time-lapse, only to pause at two points in super-slow motion. “In the Beginning was the Eye“ is also a film about cinematic time and cinematic space, about the four dimensions of cinema.

Instead of the encounter between man and landscape as in MECANO, the next very short film The Beauty is the Beast is about the intersection of man and beast, civilization and savagery. How much of the animal is in us humans and does it contribute to our cultivation?

The Beauty is the Beast operates on the interface between civilization and wilderness, nature and culture, human and animal. It raises the issue of the pros and cons of our cultivation. On the threshold between the animal inside and the civilized exterior “, the beauty” herself becomes “the beast”.

Directed by Sadeq Mousavi, the 38th Tehran international short film

festival opened in Iran Mall Cinema Complex on Oct 19 and will be

wrapped up on Oct 24. This edition of the TISFF has been approved by

the Academy Awards, popularly known as the OSCARS®, and became the

only OSCARS® qualifying festival in Iran is attended by 63 works from

19 countries and 125 directors.